The Shadow Knows

2020-05-26

Everything which is not forbidden is allowed.

–principle of English common law

Nothing is true; everything is permitted.

–Hassan i-Sabbah (attributed)

It’s a nightmare scenario: trapped behind enemy lines with no hope for rescue. For unfathomable reasons of bureaucracy, your access to Turing-complete tools of the trade has been denied. Will you fight? Or will you perish like a dog (in a mire of spreadsheets)?

Ok, that’s a little dramatic. But it’s a common-enough dilemma: due to ill-considered IT policies, you don’t have access to the tools you need to efficiently automate tedious tasks: compilers, interpreters, debuggers. You can accept defeat and turn to memorizing keyboard shortcuts… or you can join the League of Shadows.

But First, an Impassioned Plea for Sanity from our Sponsors

“Shadow IT” is right up there with the British “Shadow Chancellor” on the list of “things with a very high ratio of how cool they sound to how cool they are”. It’s a scare phrase, too often used to argue for total lockdown of an organization’s computing tools. In the parlance, “shadow IT” are all those things users do to run code without going through Channels1.

In more enlightened eras, before the current Dark Age, we called this “end-user computing” and we celebrated it. There were entire journals dedicated to academic research on making programming tools more accessible to average users, and million-dollar products aimed at that precise market.

If you are in a position to make decisions on IT policy, my plea is this: trust, but verify. It’s absolutely correct to be concerned about security threats, and to take precautions regarding the privileges users are able to exercise on your organization’s computing systems. However, many proposed policies are “technical solutions to social problems”. If you trust your employees enough to give them access to proprietary data, why not trust them to responsibly use computing tools in the most efficient way? The alternative is a self-inflicted return to inefficient and error-prone manual processes.

Furthermore, it’s not even practically possibly to deny the ability to “run code” on a general-purpose computer. That’s exactly the point of these fascinating machines: to run programs! The line between code and data, between information and interpretation, is paper-thin. Even if you white-list executables, are you sure none of the approved programs are Turing-complete interpreters themselves? Many an innocent-seeming “parser” turns out to be an interpreter for arbitrary code execution, after all.

It’s a hard problem! My (imperfect) solution? First, technical measures to enforce capabilities: access to file systems, databases, network I/O, etc. at a fine-grained level. Second, and more importantly, policies, procedures, and governance—on paper, not in code—which clearly set expectations and create the accountability that needs to accompany trust.

Let’s turn away from questions of policy and governance, and put ourselves back in the shoes of our programmer “behind enemy lines”. What options do we have, on the typical corporate Windows box, to write and execute programs?

What We Do in the Shadows

Way back in the day, many computers would boot directly to an end-user-friendly programming environment (often, a flavor of BASIC). Attitudes and expectations have changed, and neither member of the current consumer operating system duopoly provides this level of accessible programmability. However, that’s not to say that no programming tools are available even on a standard Windows installation.

The first place to check is the Microsoft .NET Framework. Bundled with Windows for quite a few versions now, .NET provides a nice programming environment for GUI and console applications on multiple platforms. The version of the .NET Framework bundled with Windows also provides compilers for the C# and Visual Basic.NET. Visual Basic still gives me flashbacks to Excel VBA macro HELL (the traditional place to On Error GoTo), so we’ll look at C#.

The C# compiler bundled with the currently-distributed version of the .NET Framework only supports the language up to version 5.0. Microsoft has been aggressively updating C# in recent years, seemingly driven by alternating jealousy of C++, then Haskell, then C++, then Haskell, and so on. In any case, C# 5.0 is a perfectly fine language for the sorts of things we’re likely to want to do.

For each language we consider, we’ll write both a “hello world” program and a simple program to copy a file from one location to another. This is to serve as a stand-in for a typical automation task, and to provide a slightly bigger taste of the language.

Our C# “hello world” (Hello.cs):

using System;

class Hello

{

public static void Main()

{

Console.WriteLine("hello world");

}

}We’ll use the C# compiler csc.exe deployed with the .NET Framework (the Visual Basic compiler is vbc.exe in the same directory), then run our program:

> C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v4.0.30319\csc.exe Hello.cs

> Hello

hello world

Here’s an example which copies the file given by the first command-line argument to the path given by the second (FileCopy.cs). I’d say “this is cheating”, but .NET really does provide a huge standard library which covers a lot of common automation tasks.

using System;

using System.IO;

class FileCopy

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

if (args.Length != 2) {

Console.Error.WriteLine("Usage: FileCopy src dst");

return;

}

File.Copy(args[0], args[1]);

}

}Again, we can compile with:

> C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v4.0.30319\csc.exe FileCopy.csWhat if .NET isn’t an option? Maybe we have a very odd Windows installation, or maybe executables are white-listed and we either lack the ability to run the compiler, or the ability to run the output executable. In that case, we’re going to need to find an existing (white-listed) executable which can serve as an interpreter. We have a few options.

First, for simple tasks, it may be possible to write a batch file, the crappier DOS/Windows cousin of a shell script. Batch files contain instructions executed directly by the Windows command shell cmd.exe. They’re frequently restricted due to their historical prevalence as a vector of e-mail attachment malware, but fundamentally they’re the right way to orchestrate execution of command-line programs on Windows.

For instance, we might create a “hello world” script (hello.bat) using echo:

@echo off

echo hello worldOr write a script which copies a file (copyfile.bat) from the first command-line argument to the second using copy:

@echo off

copy %1 %2Batch files can be run directly from the Windows command line; e.g.

> hello.bat

> copyfile.bat src.txt dst.txtWe may also have the ability to use PowerShell on more recent versions of Windows. PowerShell is a more “programmable” command shell for Windows, based on the .NET Framework and an object-oriented programming model. Unfortunately, I’m violently allergic to its syntax, so you’ll have to explore that option on your own.

Another old-school option, also unfortunately associated with “e-mail viruses”, is VBScript, a “dynamic” spin-off of (pre-.NET) Visual Basic. VBScript actually sits in a nice “sweet spot” for automating basic tasks; it’s easy to execute, has some affordances for both console I/O and simple GUIs (including lots of built-in dialog boxes), and is familiar to anyone who’s ever written an Excel macro.

We can write a “hello world” program hello.vbs:

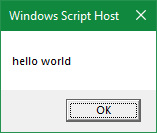

WScript.Echo "hello world"And run it either in “GUI mode” producing a dialog box, by invoking it directly from the shell:

hello.vbs

Or in “console mode” producing I/O in the terminal, using the cscript interpreter packaged with Windows:

cscript hello.vbs

Microsoft (R) Windows Script Host Version 5.812

Copyright (C) Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

hello world

We can pull in a library to write a simple file copy program (filecopy.vbs):

If WScript.Arguments.Count <> 2 Then

WScript.Echo "Usage: filecopy.vbs src dst"

Else

Dim fs

Set fs = CreateObject("Scripting.FileSystemObject")

fs.CopyFile WScript.Arguments.Item(0), WScript.Arguments.Item(1)

End IfThe VBScript interpreter is frequently blocked, but there’s a much more common Visual Basic implementation installed on most Windows machines: the Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) environment used for automating Microsoft Office. It’s most commonly used in Excel and Access; since spreadsheets are ubiquitous, we’ll focus on Excel as an “application platform” for our automation needs.

VBA is an interesting language; in some ways, it’s infuriating, but it’s also “an improvement on many of its successors” in others. I’ve written quite a bit introducing VBA as an engineering tool for an SPE webinar. It’s a statically-typed (sometimes) language with surprisingly good performance, and the ability to easily call both Win32 and COM APIs as well as launch other processes using the built-in Shell function.

A sample VBA module, for Excel, with a “hello world” (in a dialog box) function and a fancy “copy file” routine which uses Excel’s built-in dialog boxes, might look like this:

Option Explicit

Public Sub HelloWorld()

MsgBox "hello world"

End Sub

Public Sub CopyFile()

' GetOpenFilename returns False or a String, yuck

Dim src As Variant

src = Application.GetOpenFilename()

If src = False Then

Exit Sub

End If

' same for GetSaveAsFilename

Dim dst As Variant

dst = Application.GetSaveAsFilename()

If dst = False Then

Exit Sub

End If

' remember this guy from VBScript?

Dim fs As Object

Set fs = CreateObject("Scripting.FileSystemObject")

fs.CopyFile src, dst

End SubYou can get to the VBA development environment in Excel with Alt + F11. It provides an excellent set of interactive debugging tools in addition to a mediocre text editor. The example above, for instance, would be pasted into a new “Code Module”. The code can be run from the editor or by binding non-value-returning functions (Public Subs in VBA lingo) to keyboard shortcuts via Excel. Plenty of words have been spilt on Excel VBA, so I won’t elaborate here. It’s a reliable option which is usually available and capable of handling most tasks, if awkwardly.

This isn’t intended to be an exhaustive list of all the Turing-complete tools on a typical Windows installation (not to mention the many “accidentally Turing-complete” exploits we’ve surely ignored), so we’ll leave off with one “honorable mention”—the most popular programming language in the world: Javascript. It’s part of every browser, and certainly capable of doing any calculation we may require. User interface construction requires some knowledge of HTML and CSS, but that’s not a high barrier. The bigger problem for automation purposes is that, for very good reasons, browsers have become much more strict than they used to be in the bad old days about Javascript security. Accessing files on the local filesystem, making network connections to web APIs, and other “side-effecting” tasks are possible but difficult, and usually require both a running web server as well as some opt-in from the user. Still, it can be a handy option, especially for “calculator” or “scratchpad” applications.

From time to time, we may employ a synecdoche and refer to a particular lump of thus-generated source code as SHadow IT, using the traditional four-letter acronym.↩