Irregular Expressions: You Need a Parser

2020-06-22

Some people, when confronted with a problem, think “I know, I’ll use regular expressions.” Now they have two problems.

–Jamie Zawinski

When I first encountered regular expressions, while learning Perl some summer in the mid-’00s, it was a revelation. Suppose I needed (as was not uncommon that summer) to pick out oil and gas well API numbers from free-form text. API numbers come in 10, 12, and 14-digit forms; sometimes, like a credit card number or a phone number, we use little typographic flourishes like dashes or white space to separate their “stanzas” (of two, three, and five digits, followed by two optional two-digit parts). I’m not even going to try to remember the Perl syntax to attempt this without “regexes”, the part of my brain which stored those particular memories having replaced them with syntactically similar but more practical knowledge like the Japanese kanji for “big flush” and “little flush”. In short, though, you’d scan through the text, looking for a run of at least two digits. Then detect and skip any dashes or white space characters. Then check for three more digits, and so on.

Or we could write a regular expression: \d{2}[- ]?\d{3}[- ]?\d{5}([- ]?\d{2}){0,2}. That is, two digits, followed by an optional dash or space, then three digits, an optional dash or space, five digits, then anywhere from zero to two repetitions of an optional dash or space followed by two digits.

Most programming languages and many other tools support regular expressions (or “regexes”) these days; if you don’t have a text editor that supports them, or you don’t know how to use them yet, you’re really missing out! There are plenty of resources on the Internet for learning about regular expressions, and it’s a very worthwhile use of your time.

However, today I want to talk about the circumstances where regular expressions break down.

Seeing Like a State Machine

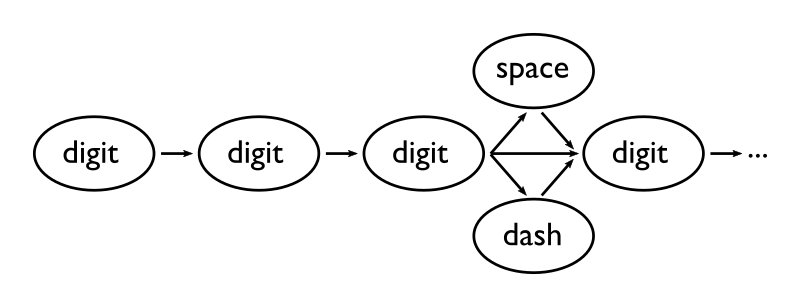

The fundamental problem with regular expressions is that they only recognize regular languages. This sounds, and is, tautological (the regular languages are often defined as exactly those defined by regular expressions), but it has huge implications. In short, regular expressions describe very simple “machines” called finite automata. These are state machines—flowcharts, if you’d like to visualize them that way. For example, here’s a flowchart illustrating the “beginning” (the first four digits) of our API-number regular expression:

Let’s think about human language for a moment. I can write a sentence, like this one, which embeds other sentences as parenthetical asides (certainly, that must include this one), quotes the utterances of others—as when Sally asked Joe, “Consider the following: ‘The horse raced past the barn fell’. Isn’t that an interesting example to parse?”—and generally meanders, digresses, and recurs. Many of these features are made possible by the fact that the grammar of English is recursive: a sentence can nest other sentences inside it, we can stack modifiers on modifiers, and so on.

The same is true of many (most?) interesting formal languages—consider the grammar of a programming language like Python, where expressions can contain sub-expressions recursively, as when we construct a nested list ([[1], [2], [3]]) or an arithmetic expression (1 + 2 * 3). We can’t write regular expressions to match these languages! Our flowchart would loop back on itself, and we’d need a scratchpad on the side to keep track of how deeply nested we were.

An Irregular Language

Let’s consider a simple little language called OBAN: the Obviously Bogus Abject Notation. An OBAN document contains a single OBAN expression denoting a value; an OBAN expression may be:

- a natural number (i.e. a non-negative integer), like

0or132141418, - a string (i.e. a piece of text), enclosed in les faux guillemets, like

<<hello world>>; a>character appearing literally inside a string must be escaped with^as in<<this string contains <<something string-like^>^>>>and a single unescaped>character inside a string is an error, - one of the three special triboolean values

True,False, andFileNotFound, - a congregation of OBAN expressions, like

(True, 12345, <<no se puede vivir sin amar>>), - or a callout of named OBAN expressions, like:

{ <<first>> ! 23

& <<second>> ! (1, FileNotFound)

& <<third>> ! { <<nested1>> ! 1 & <<nested2>> ! True }

}White space in OBAN is not significant except inside strings.

As you can see, OBAN is a language with a recursive grammar—an OBAN expression can contain nested OBAN expressions to an arbitrary depth. The full OBAN grammar is presented below in Extended Backus-Naur form:

digit = "0" | "1" | "2" | "3" | "4" | "5" | "6" | "7" | "8" | "9";

number = digit, { digit };

any_character = ? any UTF-8 code point ?

string = "<<", { (any_character - ">") | "^>" }, ">>"

triboolean = "True" | "False" | "FileNotFound";

expression = number | string | triboolean | congregation | callout

congregation = "(", [ expression, { ",", expression } ], ")"

callout = "{", [ string, "!", expression, { "&", string, "!", expression } ], "}"We know regular expressions won’t work to match this grammar1, so how can we proceed? In much the same way that regular expressions can be used to recognize regular languages, we can write recursive parsers for recursive languages. Each element of the grammar will be recognized by a function; just as the grammar recurs (as when an expression contains a callout which contains expressions), so our functions will recursively call each other. The recursive call stack will work as the “scratchpad” we need to track the depth of nesting during our parse.

Parser Combinators (mostly without the ‘M’ word)

My favorite way to write recursive descent parsers, like the one we need to parse OBAN, is to build them out of parser combinators. It’s an approach from the functional programming world. We model parsers as functions (from an input string, to a parse result); combinators (functions which operate on other functions) are then used to assemble more complex parsers out of simpler parsers.

In the interest of reaching a wider audience—and in honor of the #python IRC channel where I probably spend more time than anywhere else trying to convince people not to try using regular expressions to parse non-regular languages—we’re going to build our own parser combinators out of sticks and mud, in Python. We’ll even try to make them as well-typed as we can, under the circumstances, using mypy.

I think that I shall never see A syntax lovely as a tree

Before we start writing parsers, however, we’ll need to decide exactly what sort of structure we want to parse OBAN into. Let’s say we have an OBAN document like:

{ <<first>> ! (1, FileNotFound)

& <<second>> ! <<some <<text^>^>>>

& <<third>> ! { <<nested>> ! True }

}We’d like to turn that into something like the following Python structure:

{ 'first': [1, FileNotFound]

, 'second': 'some <<text>>'

, 'third': { 'nested': True }

}(Yes, OBAN was designed to map fairly directly onto Python’s built-in data types. If it were more exotic, we would likely want to parse it into a more explicit abstract syntax tree.)

After the customary “throat clearing” of imports, we can write a Python Enum for representing tribools:

import sys

from enum import Enum, auto

from typing import Any, Callable, Dict, List, NamedTuple, Tuple, TypeVar, Union

class TriBool(Enum):

FALSE = auto()

TRUE = auto()

FILENOTFOUND = auto()It should now be straightforward to write a “type alias” for OBAN expressions: Expression = Union[int, str, TriBool, List[Expression], Dict[str, Expression]]. However, Python’s—or rather mypy’s—type system causes a complication here. mypy “type aliases” are just ordinary Python values, and Python is a strict (that is, evaluation is “eager”—values are evaluated as the point of definition, not on-demand when they are used) language. While Python functions can be recursive, it’s much more challenging to create a recursive value in Python2. We’ll overcome this minor difficulty by taking advantage of the fact that mypy allows type annotations in class definitions to be self-referential, wrapping each “nesting” of expressions in another class instance:

class Expression:

# type alias for what we can wrap into an expression

Wrappable = Union[

int,

str,

TriBool,

List['Expression'],

Dict[str, 'Expression']

]

def __init__(self, value: Wrappable):

self.value = value

def __repr__(self):

return f'Expression({repr(self.value)})'We now have what we need to represent OBAN expressions in Python; our previous example would be:

example: Expression

example = Expression({

'first': Expression([Expression(1), Expression(TriBool.FILENOTFOUND)]),

'second': Expression('some <<text>>'),

'third': Expression({ 'nested': Expression(TriBool.TRUE) })

})Parse Me, Maybe

Now that we have a set of data types for our parser to construct, we can return to the idea of parser combinators. For this “first pass”, we’ll use a very simple approach; later, we’ll see the limitations it creates for error reporting and performance, and talk about how to overcome them.

The central idea is this: a parser is just a function which takes an input string, and returns either a “failure indicator” (we’ll use None) or, in the successful case, the parsed value and the remaining input after consuming the parsed value. In Python with mypy, that looks like:

_T = TypeVar('_T')

ParseResult = Union[Tuple[_T, str], None]

Parser = Callable[[str], ParseResult[_T]]The type Union[T, None] can also be written as Optional[T]—it’s mypy’s version of the ubiquitous “option”, “maybe”, or “nullable” type. In mypy, Union is used to create sum types: types whose values may come from of any of their component types. Unlike most statically-typed languages, we don’t need special data constructors or tags to “lift” component-type values into Union types; Python values are already type-tagged so mypy uses a subtyping relationship to model sum types—T is a sub-type of Union[T, U] and so we can assign a T directly to a variable of type Union[T, U]. The Union[T, None] type is used to model a value which is either a T or missing (None). We’ll use this simplest possible “fallible” return type for now; notice that it provides no additional information about the nature of the error in the failure case.

In a language which supported monadic types in general (like Haskell), or at least provided a monadic syntax for optional types (like Rust or C#), we’d get much of the code we’re about to write “for free”. Without venturing into the infamous “monad tutorial” quagmire, the idea behind monadic types is that we have a notion of how to chain operations on these “lifted” types together. For example, we might write a “safe division” operator in Rust as:

fn safe_div(x: f64, y: f64) -> Option<f64> {

if y == 0.0 {

None

} else {

Some(x / y)

}

}Having that, we can then easily write a function like “divide x by y and y by x, returning both results or failing if either x or y is zero”:

fn safe_div_both_ways(x: f64, y: f64) -> Option<(f64, f64)> {

safe_div(x, y)

.and_then(|x_div_y| safe_div(y, x).map(|y_div_x| (x_div_y, y_div_x)))

}We’re going to need to write our own equivalents of map and and_then (which in functional programming parlance would be called map for functors and bind for monads).

First, though, let’s define another handy type alias—the type of parsers which can’t fail.

InfallibleParser = Callable[[str], Tuple[_T, str]]Let’s write two of the most fundamental parsers.

# the simplest parser: 'match exactly this string'

def exactly(match: str) -> Parser[str]:

def parser(input: str) -> ParseResult[str]:

if input.startswith(match):

return match, input[len(match):]

return None

return parser

# another basic one: succeeds at end of input; fails otherwise

# eof: Parser[None]

eof: Parser[None]

eof = lambda input: (None, input) if len(input) == 0 else None

# a parser which consumes a single character, if available

char: Parser[str]

char = lambda input: (input[0], input[1:]) if len(input) > 0 else Noneexactly is a nice case study in the use of higher-order functions to make parser construction simple. exactly is not a parser itself, but rather a function which takes a string to match, and returns a parser (in the form of a function closing over the argument). It’s the inner closure rather than the outer function which is typed to match our definition of Parser, taking an input string and returning a ParseResult (which is just a type alias for our “optional” type). This closure checks whether the input string matches the desired string; if so, it “peels off” the input and returns it along with the remaining input. Let’s see how this works with a simple example. To “run” a parser, we just call it with the input as an argument; we’ll see how to chain parsers together in a bit.

>>> exactly('sic')('sic transit gloria mundi')

('sic', ' transit gloria mundi')

>>> exactly('this')('that')

>>>When the parser matches, we see the matched string and the remaining input; when it doesn’t, we see None3.

The eof (“end of file”) parser is even simpler: it matches when there is no remaining input. Unlike exactly, it’s a parser rather than a function for creating parsers. Notice that the parser uses None in two different ways: both as part of the successful return value (tupled with the remaining input—in this case, guaranteed to be ''), and as the failure-case return value.

char is similar, but matches any single character; it only fails if the input is exhausted.

Here’s a slightly more interesting parser-builder, and a useful parser constructed from it.

# an 'infallible' parser which consumes characters matching a predicate

def chars_while(p: Callable[[str], bool]) -> InfallibleParser[str]:

def parser(input: str) -> Tuple[str, str]:

split_at = 0

while split_at < len(input) and p(input[split_at]):

split_at += 1

return input[:split_at], input[split_at:]

return parser

# use it to build a "consume white space" parser

whitespace: Parser[str]

whitespace = chars_while(str.isspace)chars_while accepts zero or more characters for which a specified predicate function returns True; we use it with str.isspace to build a parser which strips leading white space from the input. This will come in handy later, because OBAN is a whitespace-insensitive language.

Now it’s time to write some proper parser combinators. We’ll start with the capabilities of what the typed functional programming world would call a “pointed functor”: mapping a function over the parsed result (of which replacing it with a constant is a special case), and “lifting” a value into an (infallible) parser which always returns the value.

# some basic combinators for parsers

_U = TypeVar('_U')

# map a function over a parser's result, if it succeeds

def pmap(f: Callable[[_T], _U], p: Parser[_T]) -> Parser[_U]:

def parser(input: str) -> ParseResult[_U]:

res = p(input)

if res is None:

return None

x, rest = res

return f(x), rest

return parser

# a parser which always succeeds by producing a constant

def pure(x: _T) -> InfallibleParser[_T]:

return lambda input: (x, input)

# the opposite - a parser which always fails

# it's really a Parser[_T] for all _T, but we'll use Any since mypy

# isn't that sharp

fail: Parser[Any]

fail = lambda _: None

# replace a successful result by a constant

def cmap(x: _T, p: Parser[_U]) -> Parser[_T]:

return pmap(lambda _: x, p)Let’s see how pmap (“parser map”—we don’t want to shadow the global map built-in function) works with a simple example:

>>> pmap(lambda s: s + ' semper tyrannis', exactly('sic'))('sic transit gloria mundi')

('sic semper tyrannis', ' transit gloria mundi')pure is even more straightforward:

>>> pure(23.5)('anything at all')

(23.5, 'anything at all')cmap splits the difference, succeeding with a constant value only when the underlying parser matches:

>>> cmap(True, exactly('YES'))('YES we have no bananas')

(True, ' we have no bananas')With fail, we’ve already seen a gap in the mypy type system. In Haskell, we’d type fail as (adding an explicit quantifier for clarity)

fail :: forall a . Parser amypy doesn’t let us write polymorphic values like this; in other words, we can’t really bring the _T type variable into scope in a variable definition, only in a function definition. We could expand out the definition of Parser and properly def a function for fail—but what a waste of time and lines that would be. In any case, we’re about to go where mypy can’t follow, so the types will be getting much looser from here on out.

Don’t Ever Break The chain

We’re about to start writing our first applicative parser combinators: combinators which combine the results of two or more parsers (remember, pmap just “injected” a function into a single parser). First, we’ll write two crucial combinators, which let us build parsers for both sum (that is, either/or, like Union) and product (that is, both/and, like Tuple) types, by combining parsers for their component types.

# chain multiple parsers together and produce a tuple of their results,

# if all succeed

def chain(*parsers: Parser[Any]) -> Parser[Tuple[Any, ...]]:

def parser(input: str) -> ParseResult[Tuple[Any, ...]]:

results = list()

for p in parsers:

res = p(input)

if res is None:

return None

val, input = res

results.append(val)

return tuple(results), input

return parser

# run multiple parsers, recovering from errors, until one succeeds;

# fail if all parsers fail

def alt(*parsers: Parser[Any]) -> Parser[Any]:

def parser(input: str) -> ParseResult[Any]:

for p in parsers:

res = p(input)

if res is not None:

return res

return None

return parserThese are quite a bit more complex than the parsers and combinators we’ve written before, but the logic is straightforward enough. chain applies multiple parsers, one after another, collecting their results into a tuple or failing if and when the first failure occurs in a component parser. Let’s see an example:

>>> chain(exactly('this'), exactly('that'))('thisthat')

(('this', 'that'), '')

>>> chain(exactly('this'), exactly('that'))('thisthis')

>>>The “real” type of chain isn’t possible to express in Python annotations; it should be something like “for all types T1 ... TN, takes Parser[T1] ... Parser[TN] and returns Parser[Tuple[T1 ... TN]]”.

alt applies multiple parsers until any parser succeeds; it returns the first successful result encountered, or fails if every component parser fails. We can use alt to parse value of sum types (Unions) by combining parsers for their variant types. For example:

>>> alt(exactly('this'), exactly('that'))('thisthat')

('this', 'that')

>>> alt(exactly('this'), exactly('that'))('thatthis')

('that', 'this')

>>> alt(exactly('this'), exactly('that'))('theother')

>>>Again, alt’s true type is ineffable as far as Python and mypy are concerned; it’s “for all types T1 ... TN, takes Parser[T1] ... Parser[TN] and returns Parser[Union[T1 ... TN]]”.

The next combinator could be written (inefficiently and recursively) with chain and alt, but it’s convenient to provide a more direct implementation.

# capture zero or more repetitions of a parser

def many(p: Parser[_T]) -> InfallibleParser[List[_T]]:

def parser(input: str) -> Tuple[List[_T], str]:

results: List[_T] = list()

while True:

res = p(input)

if res is None:

return results, input

val, input = res

results.append(val)

return parsermany repeatedly applies a parser, collecting as many matches as it finds (zero or more) into a list. Since the number of matches accepted by many may be zero, it is an “infallible” parser. An example:

>>> many(exactly('a'))('aaaa')

(['a', 'a', 'a', 'a'], '')

>>> many(exactly('a'))('bbbb')

([], 'bbbb')Finally, we can use alt to define a combinator which makes a parser “optional”; the result of the new parser is the result of the underlying parser if it matches, or None otherwise.

def optional(p: Parser[_T]) -> Parser[Union[_T, None]]:

return alt(p, pure(None))The Ties That bind

To finish our set of combinators—and finally assemble our OBAN parser—we need a combinator which lets us select the next parser to run based on the result of a previous parser. This ability to compose parsers in a content-aware way is the key element of a monad. Again, we wont belabor the point; there are plenty of monad tutorials, and a deep understanding of the monad abstraction is not at all necessary to make use of the bind combinator we’re about to define.

# a way to "decide" the next parser based on

# the result of the previous - this is what makes Parser a monad

def bind(p: Parser[_T], f: Callable[[_T], Parser[_U]]) -> Parser[_U]:

def parser(input: str) -> ParseResult[_U]:

res = p(input)

if res is None:

return None

x, input = res

return f(x)(input)

return parserThe general type signature of the bind operation on some monad m is (in Haskell, since the syntax for function types is prettier than Callable):

bind :: m a -> (a -> m b) -> m bWe take an “m of a” and a function which, given an a, “chooses” an “m of b” to run next; we return the chosen “m of b”.

With bind in hand, we can now make decisions inside our parsers. This lets us write some new combinators which impose additional conditions on their parsers.

# like chars_while, but requires there to be at least one matching char

def chars_while1(p: Callable[[str], bool]) -> Parser[str]:

return bind(chars_while(p), lambda c: fail if len(c) == 0 else pure(c))

# use it to build a "run of digits" parser

digits: Parser[str]

digits = chars_while1(str.isdigit)

# use it to build an "unsigned integer" parser

integer: Parser[int]

integer = pmap(int, digits)

# capture one or more repetitions of a parser

def some(p: Parser[_T]) -> Parser[List[_T]]:

return bind(many(p), lambda r: fail if len(r) == 0 else pure(r))chars_while1 is to chars_while as some is to many; both take the underlying parser and enforce the requirement that they produce at least one value (both chars_while and many are infallible and can match zero-length sequences). Using chars_while1 and pmap, we can build a parser for unsigned integers:

>>> integer('12345')

(12345, '')

>>> integer('abcdef')

>>>We’ll write a last few generic combinators with more complex behavior, which we’ll need to parse OBAN. To pick out specific pieces from the tuples returned by chain, we’ll need some “tuple-extractor” functions to use as arguments to pmap. In principle, lambda functions would be cleaner here, but mypy doesn’t seem to be able to type them correctly in this context.

# mypy hates type-checking lambdas as arguments to pmap, so we'll need some

# tuple-extractor functions

def first(t: Tuple[Any, ...]) -> Any:

return t[0]

def second(t: Tuple[Any, ...]) -> Any:

return t[1]

# "only" p - match what p matches, then insist on end-of-input

def only(p: Parser[_T]) -> Parser[_T]:

return pmap(first, chain(p, eof))

# match p, followed by optional white space

def lexeme(p: Parser[_T]) -> Parser[_T]:

return pmap(first, chain(p, white space))

# match zero or more p, separated by sep

def sep_by(p: Parser[_T], sep: Parser[_U]) -> Parser[List[_T]]:

# mypy hates this thing's type

# it should be:

# def extract(t: Union[Tuple[_T, List[Tuple[_U, _T]]], None]) -> List[_T]:

# but that fails inference when we use it as an argument to pmap

def extract(t):

if t is None:

return []

return [t[0]] + [u[1] for u in t[1]]

return pmap(

extract,

optional(chain(p, many(chain(sep, p)))))only can be used to ensure that our parser matched the entire input, with nothing left over. lexeme is a useful one for OBAN: it matches whatever the underlying parser matches, then consumes and discards any trailing white space. If we’re careful in how and where we use it, this makes matching whitespace-insensitive languages like OBAN (or C, or just about anything else other than Python) easy.

sep_by is handy for things like comma-separated lists; for example:

>>> sep_by(integer, exactly(','))('1,2,3,4')

([1, 2, 3, 4], '')

>>> sep_by(integer, exactly(','))('1 , 2 , 3 , 4')

([1], ' , 2 , 3 , 4')

>>> sep_by(lexeme(integer), lexeme(exactly(',')))('1 , 2 , 3 , 4')

([1, 2, 3, 4], '')Finally, the Easy Part

We can now piece together our complete OBAN parser in a very simple way (albeit with some awkward concessions to mypy and Python’s limitations on recursive values):

tribool: Parser[TriBool]

tribool = alt(

cmap(TriBool.FALSE, exactly('False')),

cmap(TriBool.TRUE, exactly('True')),

cmap(TriBool.FILENOTFOUND, exactly('FileNotFound'))

)

# again, mypy isn't smart enough to follow the type of this "lambda"

def _string_extract(t):

_1, parts, _2 = t

return ''.join(p[1] if isinstance(p, tuple) else p for p in parts)

string: Parser[str]

string = pmap(

_string_extract,

chain(

exactly('<<'),

many(alt(

chars_while1(lambda c: c != '>' and c != '^'),

chain(exactly('^'), char)

)),

exactly('>>')

))

# there's a circular dependency between congregation, callout, and expression

# we'll break it in expression, by making it a "proper" function

def expression(input: str) -> ParseResult[Expression]:

parser = pmap(

Expression,

lexeme(alt(integer, tribool, string, congregation, callout)))

return parser(input)

# in a lazier world, this would work:

# expression: Parser[Expression]

# expression = pmap(

# Expression,

# lexeme(alt(integer, tribool, string, congregation, callout)))

congregation: Parser[List[Expression]]

congregation = pmap(

second,

chain(

lexeme(exactly('(')),

sep_by(expression, lexeme(exactly(','))),

lexeme(exactly(')'))

))

def _callout_extract(t):

return { kv[0]: kv[2] for kv in t[1] }

callout: Parser[Dict[str, Expression]]

callout = pmap(

_callout_extract,

chain(

lexeme(exactly('{')),

sep_by(chain(

lexeme(string),

lexeme(exactly('!')),

expression

),

lexeme(exactly('&'))),

lexeme(exactly('}'))

))

# since `lexeme` skips trailing whitespace, we need to allow leading whitespace

# before a document explicitly, then ensure end-of-input

document: Parser[Expression]

document = pmap(second, chain(whitespace, only(expression)))

def main(argv: List[str]) -> int:

for line in sys.stdin:

res = document(line)

if res is None:

print('> parse error', file=sys.stderr)

else:

x, _ = res

print(f'> {x}')

return 0

if __name__ == '__main__':

sys.exit(main(sys.argv))tribool is simple: just match the fixed strings denoting each value. string uses chars_while1 in alternation with a chain for escape sequences inside a many, then combines the parts of the parsed string with a function using pmap.

The grammar of OBAN is mutually recursive: expressions include congregations and callouts, which themselves contain expressions. This mutual recursion in the grammar leads to mutual recursion in the parser. In Python, the only constructs that support this kind of mutual recursion by name are functions and classes, so in order to “break the cycle” we need to either make expression an explicit def function, or make both congregation and callout explicit def functions. For simplicity, I’ve chosen to make expression the explicitly recursive case.

congregation and callout use sep_by to handle the logic of delimited components. A document is just an expression which uses the entire input (with optional preceding white space). Our main function just reads a line at a time and attempts to parse it as an OBAN document; on success, we print the Expression object; on failure, we indicate a parse error. A few examples:

234

> Expression(234)

FileNotFound

> Expression(<TriBool.FILENOTFOUND: 3>)

xxxx

> parse error

<<xxxx>>

> Expression('xxxx')

(<<^>x^>>>, True, ())

> Expression([Expression('>x>'), Expression(<TriBool.TRUE: 2>), Expression([])])

{ <<first>> ! 23 & <<second>> ! {<<nested>> ! True} & <<third>> ! (True, False) }

> Expression({'first': Expression(23), 'second': Expression({'nested': Expression(<TriBool.TRUE: 2>)}), 'third': Expression([Expression(<TriBool.TRUE: 2>), Expression(<TriBool.FALSE: 1>)])})The parse error message is, of course, unsatisfying. Our choice to model parsers on top of the option monad means that we don’t get any additional information in the failure case. For some uses (say, parsing data from a web API whose results should be well-formed except in the case of a truly catastrophic condition), this may be totally acceptable. For interactive use by humans (say, as part of a domain-specific language compiler), this is inadequate. Next time, we’ll see how we can use a different choice of “base monad” to provide much richer error reporting.

Our implementation also has some obvious performance issues. For one, since Python strings are immutable, we’re constantly allocating and copying new strings for the remaining input after each parse step. We’ll see a faster approach next time. For another, Python is not a language which tries very hard to optimize deep call stacks or purely functional code in general. There’s less that we can do about this. To me, the tradeoff is worth it: a parser is not usually the bottleneck in the performance of a system, and the ease of reasoning about functional code outweighs the potential loss of parsing speed.

Parser Combinators in the Wild

Of course, in practice, we’d like to reach for an existing parser combinator library rather than “roll our own”. Some of my favorites are Megaparsec (for Haskell), nom (for Rust), Lightyear (for Idris), and Sprache for C#. Unfortunately, I haven’t found one I like quite as much for Python. Parsita looks promising, but I have a much lower tolerance for “magic” than required by all of the metaclasses and overloading in that library (although it does make the syntax nicer—nearly as concise as parsers in Haskell)4.

However, as we’ve seen, it’s not that hard to hand-write a minimal set of combinators to cover basic parsing needs. I’ve even done it in Excel VBA, although that was very, very tedious.

The OBAN grammar (oban.ebnf) and parser code (oban_pc_basic.py) can be viewed at https://gist.github.com/derrickturk/7ead182081f2ab1b09225fd0c11dbda9. You may also spot a “hand-written” recursive descent parser which uses a somewhat different approach: consider that a sneak preview of the next post in this series, where we’ll tackle the problems of error reporting and excessive string copying.

It’s true that some “regex” implementations go beyond the strictly regular expressions and include features for handling recursive constructs. It’s also true that many “regex” aficionados take this too far and start trying to do things like parse HTML with them, leading to the famous StackOverflow answer, with which I am fundamentally in agreement and thus will say no more about these “irregular regex” capabilities.↩

As with any language which combines indirection (pointers/references) with mutable state, it can be done, though!

↩xs = list() xs.append(xs) print(xs) print(xs[0]) print(xs[0][0]) # ... ad infinitumPython’s interactive interpreter doesn’t print anything when an expression evaluates to

None. This is so that you can call functions with no return value (which “secretly” and implicitly returnNone) without seeing output. Another fine example of Python’s “beginner-friendly” “simplicity”!↩I don’t want to rag on Parsita at all—I’ve never used it, but I’d consider it for a “real” Python parsing problem. However, it does seem to me that the “Pythonic” culture’s attitude toward complexity is a bit like the kid who, having been told to clean up her room by her parents, picks up all the junk off the floor and shoves it into the closet. It’s not the end of the world to write a couple extra lines of code, especially when the alternative is adding epicycles in the form of more indirection and more metaprogramming.↩